April 16th, 2011 § § permalink

After last week’s post about pus in semen, I thought that it might be helpful to describe another important sperm test, one that shows whether or not they’re alive.

Good sperm are alive. Not only do they swim, they live and breathe just as all living cells do. Some are dead, meaning that the ship is no longer sailing, and its motor and crew are gone.

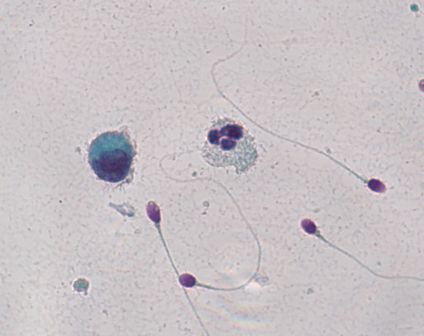

One way of figuring out whether or not sperm are alive is to dip them in colored dye. A dead sperm can’t push the dye out of its body, but a live sperm can. In the picture, the sperm are stained with a pink dye called Eosin. The dead sperm are the ones that become pink, and the live sperm are the ones that push the dye outside and stay clear (a light bluish green in the photograph.)

The result of the test is typically described in the percentage of sperm that are alive, and of course, the more living sperm the better. But even when all of the sperm are dead, a condition called “necrospermia”, couples can still conceive using in-vitro fertilization with intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

That doctors can successfully use dead sperm with in-vitro fertilization illustrates a conundrum in reproductive medicine today. The ultimate barrier to fertilization is no longer the entire sperm’s health, but the quality of its DNA cargo. Unfortunately, we don’t yet have a way of knowing the condition of a single sperm’s DNA before inserting that sperm into an egg.

So if a man’s sperm don’t wiggle, the first thing to know is whether they’re alive and sluggish or whether they’re dead. A vital stain makes that distinction. But if they’re dead, a man shouldn’t despair. Dead sperm can still be used in intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection as long as their DNA is good. Unfortunately, the only way to know that right now is to inject the sperm and to see what happens.

April 4th, 2011 § § permalink

Your semen analysis results came back, and it says that you have a lot of white blood cells. What does it mean?

White blood cells are the body’s soldiers to fight invaders like bacteria and viruses, and their presence in semen might signal an infection. White cells also produce superoxide radicals, bullets that riddle sperm and its precious DNA cargo.

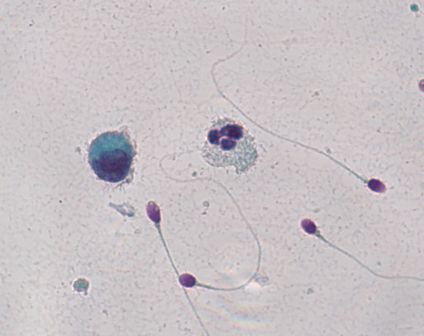

Here’s the problem: you might not have white blood cells at all. If you put semen under the microscope, white blood cells look exactly like immature sperm cells that aren’t a problem at all. A technician needs to stain the cells to see which cells are the bad actors. In the picture, an innocuous cell is on the left, and to its right lies an angry white blood cell. It’s easy to tell the difference because they’ve been stained. But without the coloration from staining, it would be impossible to say which was which.

Unfortunately, not all labs routinely stain semen if large round cells cells are present in high amounts. Specialized semen analysis labs typically will, but general laboratories performing many different kinds of tests may not.

If your test, with staining, confirms that you do have an unhealthy amount of white blood cells in the semen, what can you do? Culturing semen in the lab doesn’t usually reveal the bacterial invaders. The prostate turns out to be remarkably good at hiding infection, making it a difficult job to find the bug causing the problem. Doctors often try a course of broad spectrum antibiotics to attack anything that may be lurking. Another strategy is to use an antioxidant like coenzyme Q10 to protect the sperm from the white blood cell’s superoxide radicals.

But first you have to know if you’re dealing with white blood cells.

March 24th, 2011 § Comments Off on Big Day for Growing Sperm § permalink

It’s a big day for sperm science. In the journal Nature today, scientists from Japan describe how they were able to mature mouse sperm in a petri dish outside of the testis.

The sperm assembly line is a complicated series of steps that takes about two months from start to finish. Sperm start off as big, round immature cells called “spermatogonia” whose main job is to multiply. At some point, cells decide to turn into full-fledged sperm, becoming cells known as “spermatocytes”. A spermatocyte splits into halves, becoming a “spermatid” in a process called meiosis, which will allow its precious genetic cargo ultimately to combine with its complementary other half waiting in an egg. The spermatid half cells finally transform their shape, growing propellers, outboard motors and egg-digesting caps in becoming “spermatozoa”.

Until now, scientists were unable to get immature sperm cells to grow outside the body into those exquisitely shaped torpedo half cells. That’s where Takuya Sato and fellow scientists have succeeded. By carefully controlling the conditions for the growing sperm’s bed, these scientists discovered how to make mature sperm outside the body.

The practical implications are enormous. Sperm can be frozen before chemotherapy to spare a man’s fertility, but only from an adult man already making mature sperm. We don’t yet have a similar way to preserve the future fertility of a boy who has yet to go through puberty, and this discovery may someday allow doctors to freeze a small piece of testis from a boy about to have chemotherapy and then mature his sperm in a petri dish later in his life. For men with “maturation arrest“, where the sperm assembly line stops midstream, it might be possible to grow their sperm to completion in a petri dish, and use the grown sperm in in-vitro fertilization.

The distance between Sato and his fellow scientists’ discovery and practical use is not small. Men are different than mice, and trying to shepherd science into the doctor’s office always brings unforeseen challenges. But this discovery is a big leap for sperm science.

March 21st, 2011 § Comments Off on Radiation and Sperm § permalink

The horrific earthquake and tsunami in northern Japan remind us that no matter how powerful we become or careful we are, nature asserts itself in ways that we can’t imagine. The nuclear engineers and technicians working to contain the radiation leaking from the damaged power plant in Fukushima are nothing short of heroic. Radiation can cause all sorts of ills, from acute sickness to cancer and infertility.

In the testis, developing sperm cells are exquisitely sensitive to radiation. Kyodo News reported that after an explosion at the Fukushima No. 2 reactor on March 15, radiation levels measured as high as 8,217 micro sievert or 0.8217 rem per hour. (Micro sievert and rem are units of radiation dosage.)

Does that amount of radiation harm developing sperm cells? I asked Marvin Meistrich, Ph.D., Professor of Experimental Radiation Oncology and the Florence M. Thomas Professor of Cancer Research at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, a world’s expert in radiation and sperm. Dr. Meistrich explained that sustained exposure to 20 rem of radiation over 4 weeks caused sperm counts to drop to 1/10th of their original amount. At doses of 40-80 rem, sperm counts fell to about 1/100th of the starting number, and in some cases were wiped out entirely. At 200 rem, that drop to zero sperm became permanent. For one-time doses, Dr. Meistrich explained that 15-20 rem caused a short-term fall in sperm count, and 400 rem or more resulted in permanent loss of sperm.

We know that radiation changes DNA, the sperm’s precious genetic cargo. What we don’t know is what dose causes a harmful DNA change that damages a developing embryo or causes disease later in life.

The radiation leakage in Fukushima seems to be in the range at which damage to sperm occurs. I can only hope that the workers at Fukushima and the people near the plants are aware of the dangers and take action to protect themselves.

March 18th, 2011 § Comments Off on Freezing Sperm Before Chemotherapy § permalink

A writer for the NCI Cancer Bulletin interviewed me yesterday about Dr. Peter Schlegel’s recent article in the Journal of Clinical Oncology reporting success in getting sperm using microdissection testis sperm extraction from the testis of men who have had chemotherapy for cancer. Even if no sperm were found on testis biopsy, sperm could still be retrieved from a number of men using the microdissection technique. About two of every five men had a successful retrieval that had chemotherapy in the past.

That’s great news for the men who had chemotherapy for cancer who were lucky enough to have a successful sperm retrieval, and says a lot about how far we’ve come in retrieving sperm even in difficult conditions. But the best option would have been to have sperm frozen before beginning chemotherapy. Unfortunately, even today only about half of medical oncologists discuss freezing sperm with men before chemotherapy. There’s no good reason for that fact: a man can freeze sperm without delaying chemotherapy, and if he does, he can preserve his ability to have children in the future.

Medical oncologists save lives with cancer treatment. A life saved should be a full one, with a family if a man so desires. If you’re a medical oncologist, please talk about freezing sperm with men before beginning chemotherapy. If you’re a man facing the challenge of cancer and want to preserve your fertility, ask your doctor about freezing sperm.