June 7th, 2011 § § permalink

May blew by, and I didn’t manage a single new post. The annual meeting of the American Urological Association and a big burst of research activity in my bioengineering lab did keep me busy, but really, there’s no good excuse, and it’s time to blog again.

One very active area of this blog is How Clomid Works in Men, with over a hundred comments to date. I’m grateful to Robert for inspiring this post. His question is, are there medications that decrease estrogen?

To review how the pituitary controls the making of testosterone in the testis, testosterone is converted to the female hormone estrogen, and rising levels of estrogen tell the pituitary to make less luteinizing hormone (“LH”). The role of LH in a man is to stimulate the testis to make testosterone, and as the pituitary sees more testosterone in the blood through the lens of estrogen, it tells the testis to make less testosterone by reducing LH. I likened this negative feedback system to a thermostat and a heater: as the room becomes hotter, the thermostat turns down the heater. Clomiphene binds tightly to the pituitary, (and hypothalamus for you biological sticklers), and tricks the pituitary into thinking less estrogen is bouncing around in the bloodstream. The pituitary labors to make more LH as a result, and the testis makes more testosterone. The drug tamoxifen works in a similar way.

But Robert’s question hinted at another way to trick the pituitary: there is a way to decrease estrogen directly so that the pituitary sees less of it and makes more LH.

The enzyme aromatase turns testosterone into estrogen. Drugs like anastrozole and testolactone block aromatase, causing estrogen to decrease in the blood. The pituitary makes more LH as a result, and the testis produces more testosterone. If a man has low testosterone and high estrogen, these drugs can simultaneously increase testosterone and decrease estrogen. In a study published in the Journal of Urology in 2002, doctors Raman and Schlegel report evidence that anastrozole seems to work a little better than testolactone, at least in terms of increasing sperm production. In that study, the doctors also suggest that these drugs are best used if the ratio of testosterone is less than ten to one.

As I wrote in my post on How Clomid Works in Men, all of these drugs are off-label for use in the male, meaning that the Food and Drug Administration didn’t approve their use in men. That doesn’t mean that they can’t be used. It means that doctors need to tell patients what we know about these drugs, allowing for an informed decision on their use. It also means that many of the questions we have about these drugs don’t have answers. A good question about aromatase inhibitors in men is whether estrogen plays an important role in some health concerns in men, and if it is decreased for a long period of time, can other health problems occur? We don’t know. My current practice for prescribing aromatase inhibitors is mostly to limit their use to male fertility, and to stop the medication as soon as possible.

So there you have the two basic ways that pills can trick the pituitary into telling the testis to make more testosterone. Thanks, Robert!

April 26th, 2011 § Comments Off on Doctor’s Corner: Introducing The Blurbomatic! § permalink

|

Doctor’s Corner

|

Electronic Medical Record systems generally are terrible. Admirably intended to render doctors’ notes legible and keep records around for a while, these systems mostly slow rather than accelerate or streamline a doctor’s work. By consuming extra, precious time, these systems can get in the way of caring for a patient.

We’ve made a little gadget in our engineering lab that may help. It’s called the Blurbomatic. It’s designed to hold the blurbs that doctors write over and over and over again in Electronic Medical Record systems, so that physicians can spend less time writing and more time taking care of patients. The Blurbomatic is also a good tool for students learning how to diagnose and treat medical problems.

Right now the blurbs are all about urology, but we’d like more doctors to contribute. If you’re an interested medical professional, please check out the site, where you’ll find instructions on how to join and add blurbs. Even if you’re not an editor, you can still use the blurbs in your notes, and if you sign up, you may comment on existing blurbs.

April 16th, 2011 § § permalink

After last week’s post about pus in semen, I thought that it might be helpful to describe another important sperm test, one that shows whether or not they’re alive.

Good sperm are alive. Not only do they swim, they live and breathe just as all living cells do. Some are dead, meaning that the ship is no longer sailing, and its motor and crew are gone.

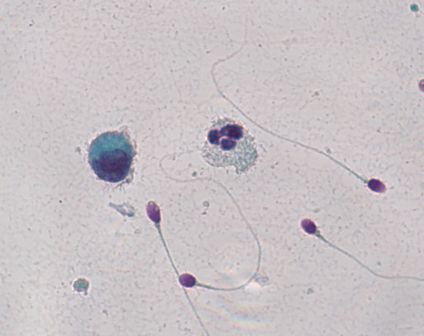

One way of figuring out whether or not sperm are alive is to dip them in colored dye. A dead sperm can’t push the dye out of its body, but a live sperm can. In the picture, the sperm are stained with a pink dye called Eosin. The dead sperm are the ones that become pink, and the live sperm are the ones that push the dye outside and stay clear (a light bluish green in the photograph.)

The result of the test is typically described in the percentage of sperm that are alive, and of course, the more living sperm the better. But even when all of the sperm are dead, a condition called “necrospermia”, couples can still conceive using in-vitro fertilization with intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

That doctors can successfully use dead sperm with in-vitro fertilization illustrates a conundrum in reproductive medicine today. The ultimate barrier to fertilization is no longer the entire sperm’s health, but the quality of its DNA cargo. Unfortunately, we don’t yet have a way of knowing the condition of a single sperm’s DNA before inserting that sperm into an egg.

So if a man’s sperm don’t wiggle, the first thing to know is whether they’re alive and sluggish or whether they’re dead. A vital stain makes that distinction. But if they’re dead, a man shouldn’t despair. Dead sperm can still be used in intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection as long as their DNA is good. Unfortunately, the only way to know that right now is to inject the sperm and to see what happens.

April 4th, 2011 § § permalink

Your semen analysis results came back, and it says that you have a lot of white blood cells. What does it mean?

White blood cells are the body’s soldiers to fight invaders like bacteria and viruses, and their presence in semen might signal an infection. White cells also produce superoxide radicals, bullets that riddle sperm and its precious DNA cargo.

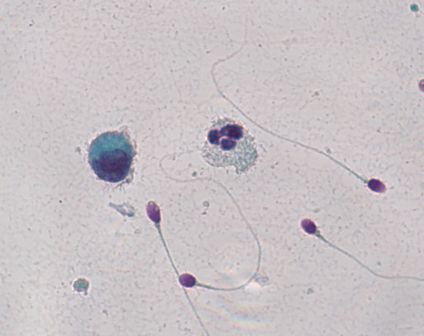

Here’s the problem: you might not have white blood cells at all. If you put semen under the microscope, white blood cells look exactly like immature sperm cells that aren’t a problem at all. A technician needs to stain the cells to see which cells are the bad actors. In the picture, an innocuous cell is on the left, and to its right lies an angry white blood cell. It’s easy to tell the difference because they’ve been stained. But without the coloration from staining, it would be impossible to say which was which.

Unfortunately, not all labs routinely stain semen if large round cells cells are present in high amounts. Specialized semen analysis labs typically will, but general laboratories performing many different kinds of tests may not.

If your test, with staining, confirms that you do have an unhealthy amount of white blood cells in the semen, what can you do? Culturing semen in the lab doesn’t usually reveal the bacterial invaders. The prostate turns out to be remarkably good at hiding infection, making it a difficult job to find the bug causing the problem. Doctors often try a course of broad spectrum antibiotics to attack anything that may be lurking. Another strategy is to use an antioxidant like coenzyme Q10 to protect the sperm from the white blood cell’s superoxide radicals.

But first you have to know if you’re dealing with white blood cells.

March 24th, 2011 § Comments Off on Big Day for Growing Sperm § permalink

It’s a big day for sperm science. In the journal Nature today, scientists from Japan describe how they were able to mature mouse sperm in a petri dish outside of the testis.

The sperm assembly line is a complicated series of steps that takes about two months from start to finish. Sperm start off as big, round immature cells called “spermatogonia” whose main job is to multiply. At some point, cells decide to turn into full-fledged sperm, becoming cells known as “spermatocytes”. A spermatocyte splits into halves, becoming a “spermatid” in a process called meiosis, which will allow its precious genetic cargo ultimately to combine with its complementary other half waiting in an egg. The spermatid half cells finally transform their shape, growing propellers, outboard motors and egg-digesting caps in becoming “spermatozoa”.

Until now, scientists were unable to get immature sperm cells to grow outside the body into those exquisitely shaped torpedo half cells. That’s where Takuya Sato and fellow scientists have succeeded. By carefully controlling the conditions for the growing sperm’s bed, these scientists discovered how to make mature sperm outside the body.

The practical implications are enormous. Sperm can be frozen before chemotherapy to spare a man’s fertility, but only from an adult man already making mature sperm. We don’t yet have a similar way to preserve the future fertility of a boy who has yet to go through puberty, and this discovery may someday allow doctors to freeze a small piece of testis from a boy about to have chemotherapy and then mature his sperm in a petri dish later in his life. For men with “maturation arrest“, where the sperm assembly line stops midstream, it might be possible to grow their sperm to completion in a petri dish, and use the grown sperm in in-vitro fertilization.

The distance between Sato and his fellow scientists’ discovery and practical use is not small. Men are different than mice, and trying to shepherd science into the doctor’s office always brings unforeseen challenges. But this discovery is a big leap for sperm science.